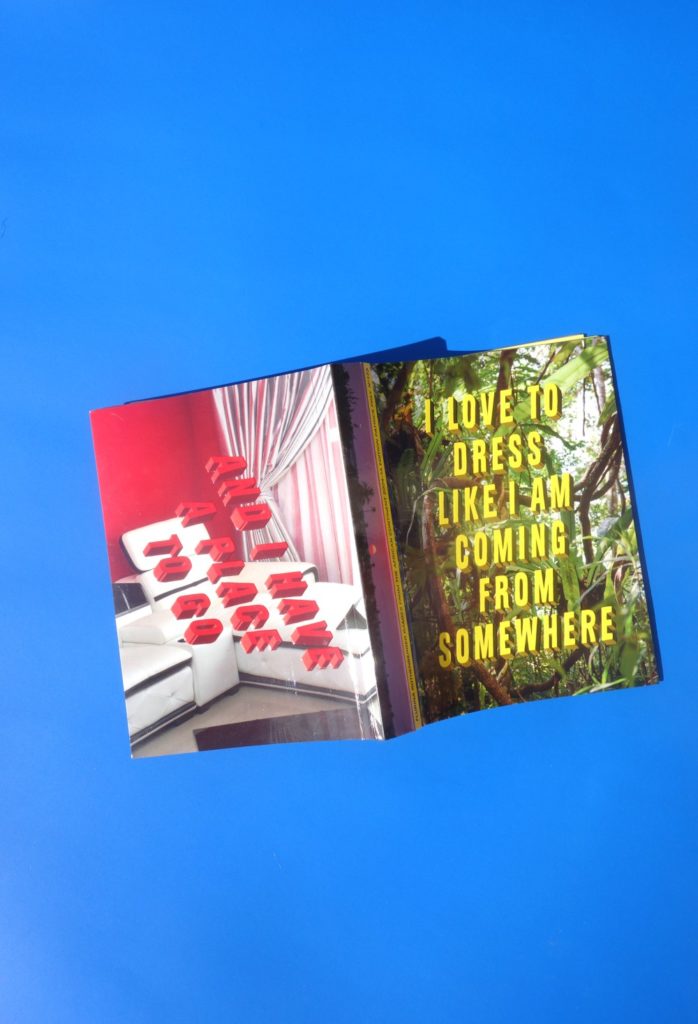

I LOVE TO DRESS LIKE I AM COMING FROM SOMEWHERE AND I HAVE A PLACE TO GO

We caught up with Flurina Rothenberger one evening last Summer at the Pinkerton in Williamsburg to talk about her book –one of Devon Hynes’s bedside book– “I love to dress like I am coming from somewhere and I have a place to go” published by Patrick Frey.

Flurina grew up in Ivory Coast before moving back in Switzerland where she studied photography. The niche book designed by Hammer is an important document as Flurina is immortalizing the precious and beauty of the every day in Africa, far away from clichés and exoticism.

Photography as an instrument of Power

Taking pictures is a gesture of power. Vulnerability is on both sides. Today when a photographer is taking a picture he can be assaulted. The African photography history is very rich and in a way has been an echo to the history of colonialism. Photography has always been a tool of power, control and repression. One of the most interesting era was the period of independence. You want to show your freedom to the world.

I was just in Myannar people love when you are taking their pictures. It’s a way for them to reinvent themselves. Now you have to know how you want to represent yourself.

What will never stop me to take pictures is to realize photography has both the power of repression and the power of liberation.”

Photography as an act of transformation

“In Africa There is no difference between fake and real. The body is not detached from the spirit.

A man who’s working at the mine in the daytime and dressing up at night and shows off in the neighborhood is not perceived as a bad thing but more like a man still with his dignity. He still get respect from his community. It doesn’t matter if your clothes belonged to a studio. You can invent yourself. Be who you want to be. A photography is always a statement.

Photography is not real to start with. It’s always a reproduction. There is always an element of transformation when we talk about photography.”

Integrity

“I can’t say to someone who’s looking at my photographs how he should look at them. But what is the most important thing to me is the relationship I have with the person I’m taking the picture of. I don’t do photojournalism I do documentary photography. The way I work is a dialogue. I always send the pictures to the people I take pictures. This is very important. Economically it can be a bit of a struggle. A lot of people ask me to buy my archives. I could make a lot of money out of it. But really, seeing my pictures out of their context will be wrong. You can change the meaning with different captions and the enchantment will be lost.

There is some magic and trust when someone you barely know let you take their pictures. I think it is beautiful. I don’t want to do something wrong with the pictures I took.”

The Future of African Photography

“African photography is very trendy. We need African photographers but nobody is trying to find them outside of Instagram. As a result we take one African photographer and we squeeze him into fashion, art and everything else. We don’t do that with Occidental photographers. African Photography should not be seen as black art.

What really makes me sad is knowing that photography is an instrument of power. It is still used to control instead to listen at what people have to say.”

Interview + Photos | Fabienne Ayina